#29. Lessons from KitKat: how the right research can build sustainable products and memorable experiences

This newsletter belongs to “The Sunday Tales Summer Edition”.

These summer letters are a bit lighter, a bit slower, just like the season.

But they’re also an opportunity: a chance to treat these months as an open campus, to learn something new, reflect on my process, and find better ways to do the work I care about.

During these past few years, I’ve come to appreciate the value of the research phase. This phase can be lost in the ‘startup buzz’, when energy is high and development moves at a rapid pace. However, when executed with care and patience, this phase can bring outstanding insights.

Research: a powerful connection between people, technology and context

If you read my newsletters regularly, you will know that I have visited Japan on a few occasions now. When I’m there, one thing that always strikes me is the wide variety of different-flavoured KitKats!

Not being a fan of flavoured chocolate, I always end up buying the original bar, in its iconic red wrapper. As any KitKat lover will know, this is simple milk chocolate. Yet in Japan, KitKat flavours range from matcha and sake, to seasonal Sakura varieties.

KitKat in Japan is a big thing, as I discovered during my first trip 8 years ago.

The story of KitKat will teach you how to conduct research in a more systematic way, encompassing not only the people (or users) involved, but also the technology and the context. Usefully, KitKat is a good example because the bar is a common product found all over the world. Whether or not you personally buy or enjoy eating KitKats, you probably know the brand well.

In fact, the success of this brand centres on how it has adapted to and understood the selling environment, going much further than standard off-the-shelf production.

Coca-Cola can tell a similar story, but KitKat is a remarkable brand because it is merely a wafer-based chocolate bar. KitKat is far from a new product on the market with a top-secret recipe. Yet the brand has superseded the success of popular local competitors (like the Japanese chocolate brand Meiji) in a very unique way that is related to people, technology, and context.

Research through three lenses: lessons from KitKat

As a word,“research” can sound abstract or academic. But research is really about observation, curiosity, and connection; concepts I will cover more deeply in my book.

The success of KitKat in Japan is a shining example of the meaning of research. Using my three lenses of research – People, Technology, and Context – we will see how KitKat turned a simple chocolate wafer bar into a cultural phenomenon!

People: the Kitto Katsu saying

Definition of People: Those who will ultimately benefit from our actions and innovations (feel, think, say).

In Japan, KitKat quickly became more than just a snack because of the reassuring sound of its name. “KitKat" is reminiscent of the Japanese phrase Kitto Katsu (きっと勝つ), which means “you will surely win". The phrase became a token of good luck during exam season for students.

KitKat observed this behaviour, quickly understanding that people were choosing their product for deeper, more meaningful reasons than mere hunger. So, in 2005, KitKat Japan launched the “Lucky Charm" campaign, which embedded the good-luck sentiment into the brand in a way that resonated deeply with students.

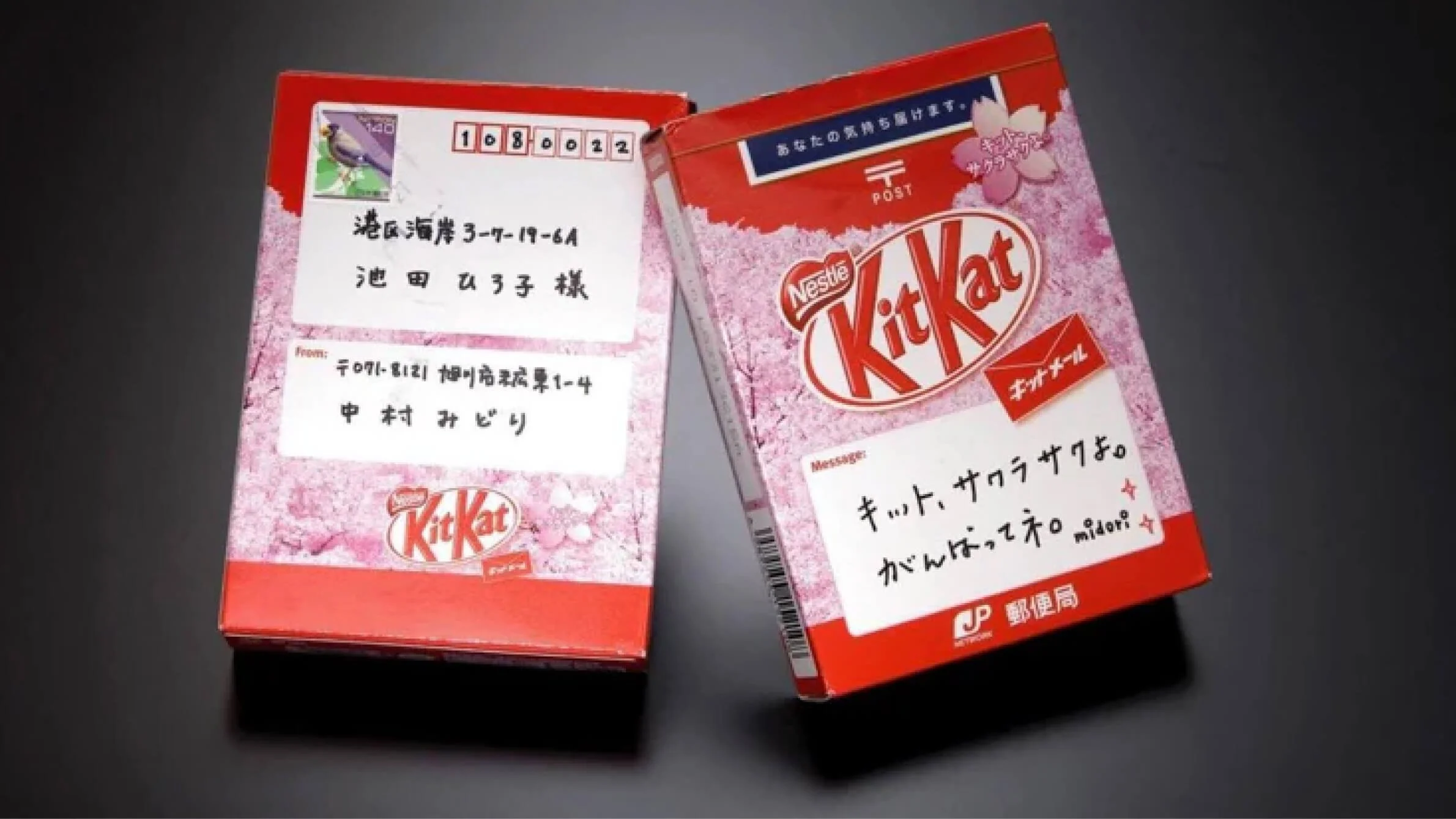

In 2009, they then partnered with Japan Post to sell special packaging that doubled as a postcard, complete with space to write uplifting messages and affix a stamp.

KitKat Japan Post. These packages flew off the shelves and won the Media Grand Prix at Cannes Lions in 2010.

There is another important Japanese tradition that KitKat made their own. This is the omiyage; the tradition of bringing gifts from a specific city or country when travelling.

KitKat embraced this by creating region-specific flavours, sold only in certain areas. In this way, a box of KitKats became a meaningful gift to bring home.

Lesson about People:

When you research the ‘people’ element of your product, recognise what is already happening and amplify it. This is what makes ideas feel natural, in a way that also makes them surprisingly disruptive.

Technology: a different palate to conquer

Definition of Technology: Devices and advancements that are crucial for realising our purpose. Accessibility and compatibility are key factors.

During my most recent trips to Japan, I’ve observed that the Japanese have a very different palate from other countries. Sweetness is subtle, textures are valued, and novelty is celebrated.

Sweets in Japan. The beautiful sweets used in the tea ceremony are not particularly sweet, but they are beautiful to look at and most of all, seasonal.

Instead of pushing the same varieties sold everywhere else, KitKat partnered with local chefs to create elaborate flavours that spoke directly to Japanese tastes, from matcha to wasabi.

This made the product compatible with the local market, adapting without imposing possibly unwelcome disruption. At the same time, these new KitKats were accessible: widely available in shops, and sold at a price point comparable to trusted brands like Meiji.

Lesson about Technology:

When researching technology, don’t add something new just because it’s new. Look at how to use existing technologies smartly, ensuring accessibility for quick adoption and iteration, and compatibility with existing networks – which will become very useful when you want to scale up.

Context: understand the physical and cultural space

Definition of Context: Recognising that our ideas exist in a larger system, we must incorporate ethical considerations into every question we ask, ensuring our path is responsible and sustainable.

Context is always bigger than both the product itself and its interaction with users.

It's about our planet, yes, but it’s also about culture. There is no perfect formula or product that covers both, and unfortunately, KitKat is a brand that lives under the Nestlè umbrella, which casts some shadows.

Yet KitKat understood the cultural recipe needed to succeed in Japan: to respect and integrate into the Japanese way of life.

As I mentioned, sweets and food in Japan are seasonal; produced with seasonal ingredients indicated as “shun" (season).

For this reason, some products become almost impossible to find, as they are limited in number and available for only a short time, thereby reducing waste and production.

KitKat understood the concept of scarcity through seasonality, and created seasonal hits that are available only at specific times of the year (by contrast, in Italy we can buy the Christmas Panettone in summer!).

The Sakura Mochi Flavour KitKat is available in spring only, to celebrate the blossom of these famous flowers.

The brand has therefore embraced Japanese culture; adapting to community values without imposing a global template.

On the sustainability side, KitKat production takes place in Japan, thereby strengthening both the economy and national identity. The production of cocoa is controlled under the Rainforest Alliance, a global NGO that uses social and market forces to protect nature and improve the lives of farmers and forest communities.

Lesson about Context:

When you research the context, think about how your product could act as an ambassador of community values, while existing responsibly within environmental and cultural limits. The goal is not just profit but resilience, creating solutions that sustain both society and the planet.

Final Thoughts

When research is performed at a deeper level, we can create products that truly stand the test of time, adapting seamlessly to change. This is because they are rooted in behaviour, and connected to a larger system.

Even if it means looking in many directions and considering various variables – which at first can seem unnecessarily time-consuming – this big-picture view ensures that if one part of that larger system collapses, we can simply pivot to others. If, for example, a cultural value fades, we can rely on other factors, whether technology or environment-based, for support. This is what makes products resilient.

By building around this systematic research, we give our ideas a greater chance of survival. They adapt not by forcing new realities, but by shaping the future out of existing values.

Want to read the first chapters of my book – for free?

I’m currently writing a book about storytelling for designers. It’s been years in the making, and I’m finally ready to share it, one chapter at a time.

Join my newsletter The Sunday Tales to become one of the first readers. You’ll get exclusive access to the early drafts, plus the chance to help shape the book through your thoughts and feedback.