#13. The Dollhouses of Frances Glessner Lee

From the section "The Story That Saved the Day” of The Sunday Tales.

The Story that Saved the Day is a section of The Sunday Tales that will inspire you through recounting fantastic brand stories. What makes them fantastic? Each of the featured brands were "saved" by implementing storytelling elements and methodologies in their business. Taken from a variety of industries and standpoints, these stories will show you how storytelling is a flexible and adaptable tool that, if used correctly, can produce exciting concepts and incredible achievements.

Along with some storytelling methodologies, I will also list some takeaways and lessons we can learn from each brand story. So get ready to take notes!

I would like to dedicate the last issue of the year to Frances Glessner Lee, a woman I admire for her tenacity, innovative approach, and creativity.

Her name may be unfamiliar to you; it certainly was to me until a few years ago. Then, I visited a forensic science exhibition in London. Among the biographies of serial killers, medical tools, and chemical substances, I discovered a room dedicated to what resembled dollhouses under glass. Their purpose was sinister and unsettling, as each one meticulously recreated a crime scene.

I soon discovered that this room housed a collection of some of Frances Glessner Lee's remarkable work. Her dioramas revolutionised crime investigation, by training detectives to follow the movements of a serial killer within the crime scene.

In this issue, I want to explore the importance of building scenarios for UX designers, and highlight essential lessons we can learn from the work of this incredible woman, who is often referred to as “the mother of forensic science."

The only woman in the room

Frances Glessner Lee was born to a wealthy Chicago family in 1878. She wanted to study medicine, but instead married Blewett Lee – the law partner of her brother’s friend – when she was 19. Although Frances would give her husband three children, she was destined to become more than an ordinary wife and mother.

In a world that told women to stay at home and tend to their families, Lee saw an opportunity to use her traditional “woman's skills" in a productive way. She sought to change the way investigations were conducted, at a time when the field of forensics was in its infancy.

The “Nutshells", as she called them, were miniature, scaled reproductions of individual crime scenes. They look like innocent dollhouses, until you notice the finer details: a splatter of blood on the carpet, a little doll with a knife stubbed into her chest, or a bullet hole in the wall.

The Nutshells. Lee sewed the curtains, designed the wallpaper, and painted miniature portraits for décor in these dollhouses. She used pins and a magnifying glass to knit clothes, and a lithographic printing method to reproduce minuscule newspapers.

In 1943, 25 years before female police officers were allowed out in patrol cars, the New Hampshire State Police commissioned Lee as its first female police captain and educational director.She was also training young detectives at Harvard University, in the Department of Legal Medicine.

As a woman stepping outside of her socially-accepted position of mother and homemaker, Lee understood the narrative nature of death better than most.

Inspired by Lee, here are three lessons I want to share. Each one can help you create better products, without “killing" the wider experience.

The Context: every element shapes the meaning of the experience

Crime scenes are complicated, and so are the experiences we design for our users. Lee said that she was “constantly tempted to add more clues and details,” but also that she restrained herself so that the Nutshells wouldn’t get too “gadgety.”

Every object in Lee's dioramas told a story, but their meaning depended on the broader context. For example, a misplaced chair or a torn curtain only made sense in relation to other elements in the scene.

In the same way, UX designers must create designs that consider the specific context, while also understanding the overall experience. Providing timely feedback during key moments of user interaction, or incorporating a clear call-to-action (CTA) after a specific action, are essential elements that define the narrative of the product. These components must be strategically placed to ensure they integrate with the rest of the experience.

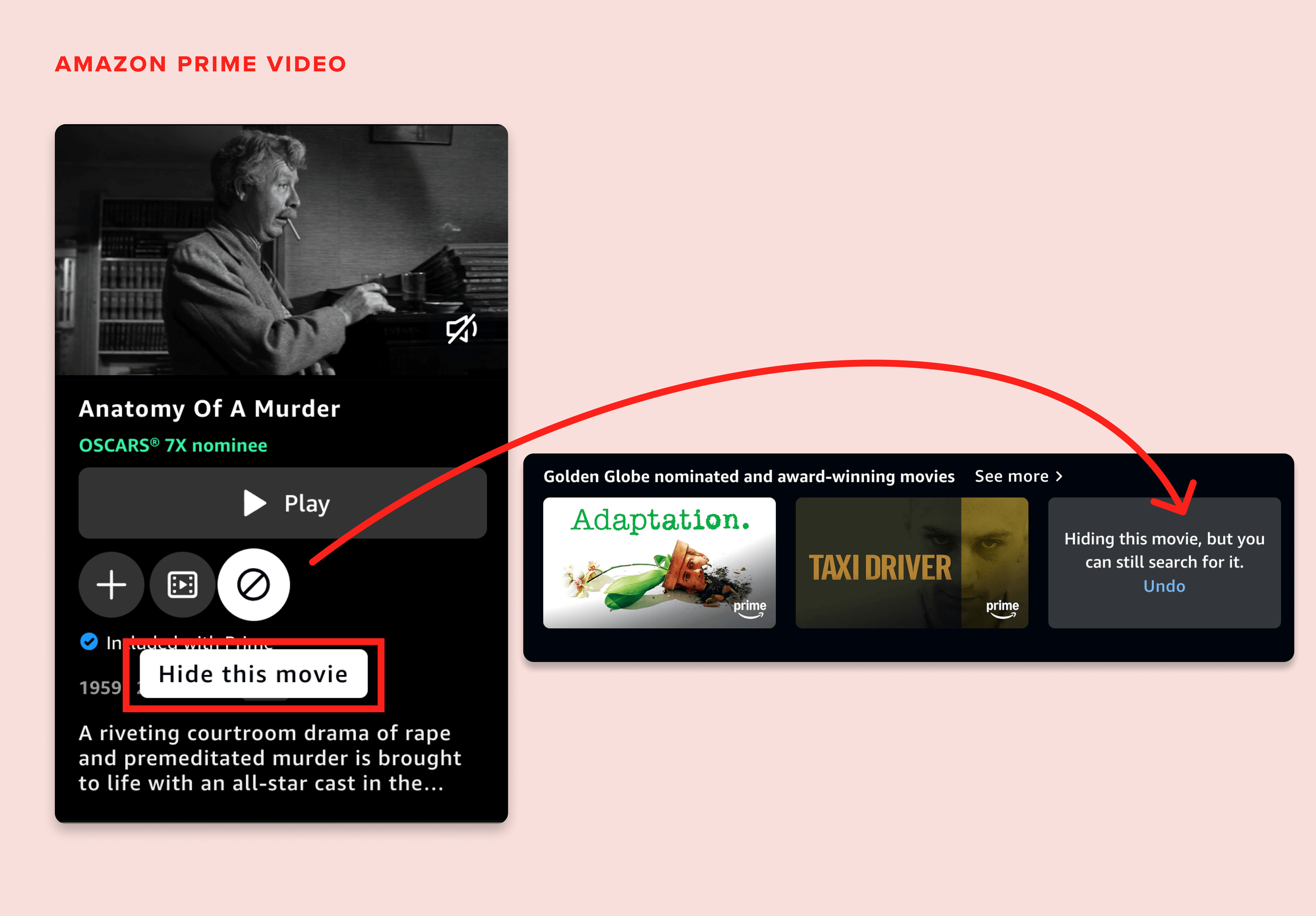

I was always curious about what the “hide the movie" feature on Amazon Prime does. Afraid of losing my movie options, I decided to try it out while looking for a film to watch with my 3-year-old nephew and better filter our research. While “hide the movie” does indeed hide a movie from your list, a reassuring banner appears, allowing you to undo this action at any time.

Amazon Prime Video: the “hide the movie”action does hide a movie from your list, but a reassuring banner appears, allowing you to undo this action at any time.

Another example of context is the Slack notification that tells you it’s too early for the user to read the message, due to her time zone. The notification is designed to inform without distracting from your main action: sending a message.

The discreet Slack notification: the banner tells you it’s too early for the user to read the message, due to her time zone. But it allows you to perform the primary action to send a message.

The Interactions: make the user central to your scene

Lee's dioramas weren't passive art. They were active puzzles, inviting investigators to think critically and piece together the story. In fact, her dioramas were used to train future investigators, and while VR and 1:1 reproductions of crime scenes are often used today, Lee was instrumental to ensuring investigators could interact with these scenes in a more immersive way.

In the same way, UX designers should design for interactivity. If a user feels like an active participant, the experience – and the product – become more memorable. It can be tempting to think of complex interactivities right away, but you can start small by adding customisations, guided onboarding, progress trackers, or even gamification, to foster a sense of involvement and achievement.

There aren’t many banks that show the impact of your investments (whether fictional or not!), but the Neon Green interface does just that. Every time you add money to your bank account, a new tree grows in your virtual field.

The Neon Green interface: every time you add money to your bank account, a new tree grows in your virtual field.

Learning apps emphasise interactivity, as this is essential for keeping users accountable as they learn.

Duolingo, for example, has enhanced its learning experience by incorporating a social aspect, allowing users to connect with friends, participate in quests, receive nudges, and engage in more interactivity, including listening and speaking exercises. It also lets you personalise your app icon, so the experience feels even more real.

The Duolingo interface: larger groups can share the listing, chat on a common messaging channel and create a collaborative listing too.

The Audience: challenge their assumptions

The imprecision of the human mind can derail justice. As Lee wrote in 1952, “far too often the investigator ‘has a hunch,’ and looks for and finds only the evidence to support it, disregarding any other evidence that may be present.”

Lee’s dioramas were crafted to highlight biases or common investigative oversights, forcing observers to challenge their initial assumptions and look deeper. For this reason, Lee hoped that the scene's staging would help investigators look for evidence, rather than imagine it.

In this lies an important lesson for UX designers: don't settle for the obvious. Challenge common user assumptions with innovative design patterns that nudge them towards exploration and learning.

By understanding how a user interacts with a specific product (use the UX Dramaturgy to analyse the different ways a user might interact with your product), we can jump ahead of an ‘ordinary’ experience, prevent errors, and make your product truly remarkable for the user.

You could also re-invent collaborative features used by iconic apps (like Pinterest collaborative boards or Figma design app) to enhance your product experience, exactly as Airbnb has done with its Groups feature. According to Airbnb “more than 80% of bookings on Airbnb are group trips, but the app wasn’t designed for groups.” Since summer 2024, it’s possible to collaboratively plan your holidays with a larger group via Airbnb, to avoid one person being blamed for booking the wrong listing!

The Airbnb group booking feature: larger groups can share the listing, chat on a common messaging channel and create a collaborative listing too.

Last thoughts

Before Frances Glassner Lee's diorama, investigators received little training. This meant they often overlooked or mishandled key evidence, were derailed by their bias, or irrevocably tampered with crime scenes.

Lee and her colleagues at Harvard worked to change this view by introducing intuitive but innovative ways to analyse, test, and re-define the narrative of crime.

Crime scenes are complicated, and so are the experiences we design for products. For this reason, the work Lee is a reminder that constant iteration, testing prototypes, gathering feedback, and refining continuously are the keys to creating an effective experience that helps the user achieve her purpose.

Did you enjoy what you just read? Subscribe to my Sunday Tales Newsletter!

The Sunday Tales is an initiative that was requested by many of the 2000+ students from my Domestika course. They wanted to know more about storytelling, but didn't know where to find the right information.

At the same time, I realised that many storytelling-related elements need to unfold clearly in my mind. Writing about them seemed like the ideal solution. That’s why I would be extremely grateful if you subscribed to this newsletter!

Your support will help Sunday Tales grow, and I hope you will always come away feeling informed and inspired.